|

The Highland Clearances are a notorious part of Scottish history, but what do most of us really know about them? Most people probably associate the clearances with the aftermath of Culloden, when the Duke of Cumberland and his troops carried out their murderous actions across the highlands, orders which were sanctioned by the Hanoverian/British establishment formed in 1707 through the act of Union. The orders given were an attempt to eradicate the Clan and Highland way of life as well as capturing the Prince who was in hiding. This is quite an accurate assumption, but after researching the subject I found that it was only the tip of the ice-berg and only the beginning to what is known as the “Highland Clearances”. I hope the web pages covering the subject can be enlightening and give a more in depth understanding and feeling, as well as being eye opening to the truths, the atrocities, of events and true accounts of what actually happened, which made the Highland Clearances so notorious.

The brutal legacy of the mid- late 18th and early 19th centuries are still etched in the minds of the people of the Highlands today. Man’s inhumanity was brought sharply into focus, when entire communities were swept away so that the land could be sold off to southern sheep farmers. |

|

During what became known as the ''Highland Clearances'', it was not just a hundred or so victims who suffered eviction, but tens of thousands of men, women and children alike often violently, from their homes to make way for large scale sheep farming. It is fair to say that, had it not been for the Jacobite defeat at the Battle of Culloden and the actions that were carried out by the Duke of Cumberland on behalf of the English/British crown that the Highland Clearances may never have come to the same fruition or grown to the same extent in which they had. Although the aftermath of Culloden was a major factor, emigration had actually begun after the 1715 Rising, it is also fair to say that some Clan Chief’s and Landowners had been dealing with foreign landowners some years earlier although these were on a very small scale compared to what would happen in years to come. |

| What the landlords thought of as necessary "improvements", later to become known as the Clearances , are thought to have been begun by Admiral John Ross of Balnagowan Castle in Scotland in 1762, although MacLeod of MacLeod (i.e. the chief of MacLeod) had done some experimental work on Skye.

In 1732 and 1739 -- Macleod of Dunvegan and MacDonald of Sleat sold selected Clan members as indentured servants to landowners in the Carolinas. [see documents and letters ].

A prediction of the clearances was made in the 13th Century -- The Seer Thomas of Erceldoune (a.k.a. Thomas the Rhymer or True Thomas) reportedly prophesied about the Highlands:"The teeth of the sheep shall lay the (useless) plough up on the shelf." Approximately 350 years later, Coinneach Odhar, the Brahan Seer, expanded on Thomas' vision:

“The day will come when the Big Sheep will put the plough up in the rafters... ...the Big Sheep will overrun the country till they meet the Northern Sea... ...(and) in the end, old men shall return from new lands...”

|

|

Although the clearances may have been predicted as early as the 13th century and noticeably began after the 1715 rising, real indications do suggest that plans of British establishment control over the clans and the highlands began before the Union of the Parliaments in 1707 to as early as 1688 if not before, when King James VII went into exile. The evidence from the events surrounding and the carrying out of the Massacre of Glencoe in 1692 are a prime example. It is also quite noticeable to see through research that the main clearance areas also coincidentally seem to be lands that had either been forfeited to the British establishment by those who supported the Jacobite cause or had some other Jacobite connection.

There may have well been a religious element in the clearance areas as well for a majority of those who were victims were Roman Catholic. Although a very large movement of Highland settlers to the Cape Fear region of North Carolina, however, were Presbyterian. (This is evidenced even today in the presence and extent of Presbyterian congregations and adherents in the region.)

From the late 16th century the required clan leaders had to regularly travel to Edinburgh to provide bonds for the conduct of anyone on their territory, bringing a tendency among Chiefs to see themselves as landlords. The lesser clan-gentry increasingly took up droving, taking cattle a long the old unpaved drove roads to sell in the Lowlands. This brought them wealth and land-ownership within the clan, though the Highlands did have problems of overpopulation and poverty. With various new laws brought in from England as part of the act of Union 1707, this led to numerous various oppressions, which led to uprisings. The Jacobite Risings of 1715 and 1719 brought repeated British government efforts to curb the clans, new acts were passed to try and prevent other risings.

|

| From around 1725, in the aftermath of the Jacobite Rising known as the 'Fifteen’, clansmen had began emigrating to the Americas in increasing numbers. The earlier Disarming Act and the Clan Act made ineffectual attempts to subdue the Scottish Highlands, so eventually troops were sent in. Government garrisons were built or extended in the Great Glen at Inverlochy [ later named Fort William], Kiliwhimin (later renamed Fort Augustus) and Fort George in Inverness [ later to be re-located in 1752 to the present site over looking the Moray Firth], as well as barracks at Ruthven, Bernera, Corgarff and Inversnaid, linked to the south by the Wade roads constructed by Major-General George Wade, these roads were nick named the chain, because of the links created to the various garrisons. These had the effect of limiting organisational travel and

choking off news and so further isolated the clans and limited the unrest to local outbreaks although the clans actually made good use of the roads themselves to one extent or the other, nonetheless, things remained unsettled over the whole decade.

In 1725 Wade raised the independent companies of the Black Watch as a militia to keep peace in the unruly Highlands, which was also a factor on the increasing droves of clansmen now emigrating to the Americas. Increasing demand in Britain for cattle and sheep and the creation of new breeds of sheep, such as the black faced which could be reared in the mountainous country gave the landowners and Chiefs the opportunity of higher rents to meet the burden of costs of an aristocratic lifestyle. As a result, many families living on a subsistence level were displaced exacerbating the unsettled social climate. The various pressures which were mounting lead to another rising “The 45”. This rising was to be so different, although the ultimate battle was at Culloden [Drummossie] Muir there was to be an aftermath that would be far worse than the battle itself.

The years which followed the defeat at the Battle of Culloden |

After the defeat at the Battle of Culloden [Drummossie ] orders were issued from George II to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, general of the Hanoverian/British army to break the clan system and make sure another rising would never happen again. Cumberland carried out the orders giving no quarter to almost anyone he and his men came across, regardless if they were even involved in the battle or not. His brutal actions would later earn him the nickname of the “Butcher”. In the following months Cumberland’s troops swept all over the highlands burning, murdering, raping, cattle stealing, thieving from all those that were suspected of supporting the Stewart cause.

|

|

|

Although Jacobite supporters were being hunted the real prize was Charles Edward Stewart [Bonnie Prince Charlie] who was in hiding, harbouring a 30,000 pounds sum on his head, the equivalent to 3 million today. The hunt stretched as far as the outer Hebrides, which in some cases the people never even knew about the battle at Culloden[ Drummossie] or that it had even been fought. Following the battle, those who were captured and taken prisoner were not all instantly condemned to death, surviving Highlanders and Clan Chiefs were sent to the Caribbean as slaves, as well as being sent to London, Brampton, Carlisle, York for imprisonment or execution or both. |

Those who had lands and estates had to forfeit them under the Forfeited Estates Act of 1707, an English custom which was introduced into Scotland when the Union was formed, coincidently the same year.

When Charles Edward Stewart set sail from Loch Nan Uamh, he took with him not only the Jacobite cause, but the hope of a nation. Others followed the Prince into exile, such as Lord George Murray and Cameron of Locheil. Other Acts of Parliament were brought in to destroy what was only the beginning of the establishment’s plan, to eradicate the clan system and highland way of life. |

1747 -- The Act of Proscription was introduced which was to ban the wearing of tartan, the teaching of Gaelic, the right of Highlanders to "gather," and the playing of bagpipes in Scotland.

1747 -- The Heritable Jurisdictions Act forced Highland landowners to either accept all English rule or else forfeit their lands. Many Highland landowners and Clan chiefs moved to London.

Because of the two acts above it left the Clan Chiefs and their Kin with decisions to make about their future. Some took the decision to emigrate to the land of promise in which they thought would lead to a better life. Fighting men who had been so heroic in battle and fought against the British Crown found them selves being forced to join the British army, not because they changed loyalty, but for the money and because they had no other option as it was the only thing they knew.

Although this was not always the case, some suffered from new parliamentary acts introduced over the years, introduced by the unwanted Union in 1707 with England, which would bring even further hardships. Those who had taken the Kings shilling and those who bought the forfeited lands and estates took advantage of their situation knowing fine well they would have the support of King George II.

1746 (April) -- Following the Battle of Culloden, surviving Highlanders are sent to the Caribbean as slaves.

1762 -- Sir John Lockhart-Ross brings sheep to his Balnagowan estate, raises tenant rents, installs fences and Lowlander shepherds.

1782 -- Thomas Gillespie and Henry Gibson lease a sheep-walk at Loch Quoich, removing more than 500 tenants, most of who emigrate to Canada.

1782 -- The Act of Proscription is repealed, but many Highland landowners, who have been born and raised in London or other metropolitan areas, remain in their urban homes, distancing themselves from the tenant Clan members on their lands. |

|

1780s (late) -- Donald Cameron of Lochiel begins clearing his family lands, which span from Loch Leven to Loch Arkaig.

1791 --The Society of the Propagation of Christian Knowledge reports that over the previous 19 years more than 6,400 people emigrated from the Inverness and Ross areas.

1791 -- "The dis-peopling in great measure of large tracts of country in order to make room for sheep (is taking place)," observes the Reverend Kemp after visiting the Highlands.

1792 -- Sir John Sinclair of Ulbster brings the first Cheviot Sheep to his Caithness estates. These sheep would later be referred to as four-footed Clansmen, indicating the tenants' rage at being removed in favour of animals.

1792 (late July to early August) -- Angry tenant farmers drive all the Cheviots in Ross-shire to Boath. The 42nd Regiment intervenes, and the sheep are returned to Ross-shire.

There is no doubt that in the years after 1745, British authorities acted to suppress the clan loyalties in the Highlands. Culminating after the 1745 Battle of Culloden with brutal repression including prohibitions against the wearing of traditional highland dress, the bagpipes, and other related legislation from 1746 on leading to the destruction of the traditional clan system and of the supportive social structures of small agricultural townships. The warrior culture of the Highlands was re-diverted as Highlanders were recruited as soldiers to serve in the wider British Empire. Clan Chiefs were encouraged to consider themselves as owners of the land in their control, in the English manner - it was previously considered common to the clan.

The Clan system and way of life although not realised at the time, was beginning to die with Culloden and the 1745 Jacobite Rising. |

|

The clans from north of the River Tay were to notice this to a greater extent in the years that were to follow than those from the lower parts of Scotland, as the highland clans had not been subject to the same English transformations.

The stories of the Highland Clearances are endless, whether they are individual cases or something that effected whole communities. Although the clearances are associated with the Highlands there were other parts of Scotland which suffered as well, like Argyll and Perthshire, not to the same extent as the likes of Sutherland in north east Scotland, but they were cleared never the less. To get a true picture of what inhumanity and sufferings that were endured, it would be injustice to leave out any of the accounts that took place. Although there are many cases, many of which we are lucky enough to have documented and can be quite a lot to read, they give us stark reminder of what suffering was endured and created by man himself.

[See the various sub sections]

Rural England had already experienced areas of depopulation in the British Agricultural Revolution, but no where near to the extent of what the Highlands would experience. Similar developments began in Scotland to that of rural England in the Lowlands, called the Lowland Clearances, Many of the Lowland areas were being transformed and had been part Englisized some years earlier. This Scottish Agricultural Revolution was changing the face of the Scottish Lowlands and transformed the traditional system of subsistence farming into a stable and productive agricultural system. This also had effects on population and precipitated a migration of Lowlanders, now recognised as the "Lowland Clearances".Internationally, Scotland's fate was tied to that of the United Kingdom as a whole. Shortly after Culloden, Britain successfully fought the Seven Years' War (1756 – 1763), demonstrating its rising significance as a great power. As a partner in the new Britain, parts of Scotland began to flourish in ways that she never had as an independent nation. As the memory of the Jacobite Rising faded away, the 1770s and 80s saw the repeal of much of the draconian laws passed earlier. Most were repealed by 1792 as the Episcopalian and Catholic clergy no longer refused to pray for the reigning monarch, although Unitarians were still affected.

John Leyden, Tour in the Highlands and Western Islands, 1800

Despite the emigration, the population of every highland county increased between 1755 and 1821. Population was not the only thing on the way up. Rent was increasing and ordinary people found it more and more difficult to pay. The clearances did not just affect the highlands, other parts of Scotland suffered as well. Towards the end of the 18th century ships were leaving from all parts of Scotland with those who were being forced to leave in one way or another.

Some lowland areas began to see great cities emerging, like Glasgow and Edinburgh who in later years would see a swell in population with the influx of emigrants. Economically, Glasgow and Edinburgh began to grow at a tremendous rate at the end of the 18th century. The Scottish Renaissance was one of philosophy and science. The Scottish Enlightenment involved names such as Adam Smith, David Hume and James Boswell. Scientific progress was led by James Hutton and William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin and James Watt (instrument maker to Glasgow University). These cities had been introduced to English customs through trading andindustrialism, Lowland Scotland turned more and more towards heavy industry. Glasgow and River Clyde became a major ship-building centre. Glasgow became one of the largest cities in the world, and known as "the Second City of Empire" after London, where the Highlands had not changed. In the Highlands they had managed to keep hold of their traditional ways throughout the centuries. A main contributing fact is most certainly the distance geographically from the border between England and Scotland to both the Lowland and Highland areas of Scotland. Although Scotland is one country, we have the terminology of classing a seamless divisional boundary into the Highlands and Lowlands, this came about centuries before [ see web pages on the gaelic language ].The Highlands were always seen as a barbarious and rough area, but this was only because the folk who lived and worked the land were set in their ways and didn’t care for change, living their life in a way which had seen very little change from century to century before them. As far as the Highlands the impact on a Goidelic (Scottish Gaelic)-speaking semi-feudal culture that still expected obligations from a chieftain to his clan led to vocal campaigning. There was a lingering bitterness among the descendants of the large numbers forced to emigrate, or to remain and subsist in crofting townships on very small areas of often marginal land. Crofters became a source of virtually free labour to their landlords, forced to work long hours, for example, in the harvesting and processing of kelp.

To landlords, 'improvement' and 'clearance' did not necessarily mean depopulation. At least until the 1820s, when there were steep falls in the price of kelp, landlords wanted to create pools of cheap or virtually free labour, supplied by families subsisting in new crofting townships. Kelp collection and processing was a very profitable way of using this labour, and landlords petitioned successfully for legislation designed to stop emigration. This took the form of the Passenger Vessels Act passed in 1803. Attitudes changed during the 1820s and for many landlords, the potato famine which began in 1846 became another reason for encouraging or forcing emigration and depopulation. |

As the rest of Britain was waking up to a new era of civilisation and enlightenment, greedy landlords of lands and estates in the Highlands of Scotland began to remove the local people to make way for sheep. Sheep were given priority over people, but not just any people, for the folk burned out of their homes were the descendants of the clansmen, the native people of the land - the highlanders, of those who fought or fell in previous campaigns.

Fuadaich nan Gàidheal, the expulsion of the Gael, is a name given to the forced displacement of the population of the Scottish Highlands from their ancient ways of warrior clan subsistence farming, leading to mass emigration from the Highlands to the coast, the Scottish Lowlands, and abroad. This was part of a process of agricultural change throughout the United Kingdom, but the late timing, the lack of legal protection for year-by-year tenants under Scottish law, the abruptness of the change from the clan system and the brutality of many of the evictions gave the Highland Clearances particular notoriety.

Many chiefs engaged Lowland, or sometimes English, factors with expertise in more profitable sheep farming, and they 'encouraged', sometimes forcibly, the population to move off suitable land. 1792, infamously known as the Year of the Sheep, also signalled another wave of mass emigration of Scottish Highlanders. The people were accommodated in poor crofts or small farms in coastal areas where farming could not sustain the communities and they were expected to take up fishing. Population fell significantly in some areas, where large numbers of Highlanders relocated to the lowland cities, becoming the labour force for the emerging industrial revolution, many emigrated to other parts of the British Empire, particularly Nova Scotia, the Eastern Townships of Quebec, and Upper Canada (later known as Ontario). Antigonish and Pictou counties and later Cape Breton, the Kingston area of Ontario and the Carolinas of the American colonies.

'Never again will a single story be told as though it is the only one' - John Berger. The Highland Clearances are stories of individual people, in some cases of their greed and in others of their suffering.

|

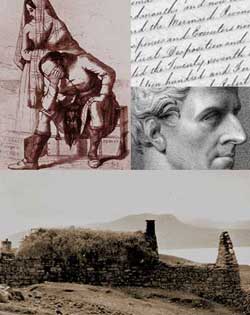

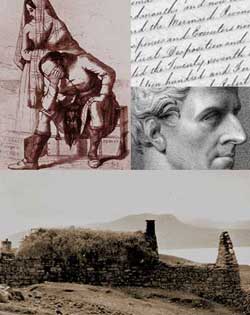

| Life in the highlands was tough and anyone with an impression of a bonnie wee highland village where everyone was happy couldn't be more inaccurate. Most people had taken to growing potatoes, which provided more food but were vulnerable to disease and crop failure. The houses themselves consisted of a one-level stone dwelling, with some rough wooden rafters and thatched with turf. The fire was in the middle of the room and smoke escaped through a hole in the roof. Rough living, compared to those in Edinburgh! In fact, emigration was already happening to a degree in the Highlands, where people chose for themselves to leave their homeland for pastures in the new world. |

|

| |

HIGHLAND DWELLINGS

By a house, I mean a building with one storey over another; by a hut, a dwelling with only one floor. The laird, the tacks man and the minister have commonly houses. Wherever there is a house, the stranger finds a welcome.

The wall of a common hut is always built without mortar by a skilful adaptation of loose stones. Sometimes a double wall of stones is raised and the intermediate space is filled with earth. The air is thus completely excluded. Some walls are, I think, formed of turf. Of the meanest huts, the first room is lighted by the entrance, and the second by the smoke hole. The fire is usually made in the middle.

There are huts, or dwellings, of only one storey, inhabited by gentlemen, which have walls cemented with mortar, glass windows, and boarded floors. Of these, all have chimneys, and some chimneys have grates.

Dr Samuel Johnson

Journey to the Western Islands, 1773

The houses of the peasants in Mull are most deplorable. Some of the doors are hardly four feet high and the houses themselves, composed of earthen sods, in many instances are scarcely twelve. There is often no other outlet of smoke but at the door, the consequence of which is that the women are more squalid and dirty than the men and their features more disagreeable.

John Leyden

Tour in the Highlands and the Western Isles, 1800

Some who were evicted from their houses were lucky in the first removals of tenants, a small compensation of 30 pence in two separate sums was allowed for houses destroyed. Some of the ejected tenants were also allowed small allotments of land, on which they were to build houses at their own expense, no assistance being given for that purpose, perhaps it was owing to this that some were reluctant to move until they had built their new houses, which can be seen as quite understandable.

|

|

You could imagine today if you were to be evicted from your abode, given very little or no notice, possessions removed from your home and dumped outside, regardless of the weather condition, then left to think where your shelter would be for night etc with all your belongings around you with no way of storing them. Surplus to this you may have to travel possibly thirty to fifty miles to relocate to a new found home, little or no more than a horse and cart for transportation to do so. Then having to build shelter first or even then to find that you are forced to board a ship for foreign shores not knowing what will be at the other end.

|

Boarding a ship for a foreign shore was for some a new start to life, a new adventure, but to others it was seen as being forced to move from a land that they had known all their lives, a land that they had been born and bred, which had been held for centuries by generations of their ancestors, folk who were set in their ways and even some who had fought and died for land. What was considered home to families were no more than simple dwellings.

Near Taynish in Argyll, ridges of potatoes appeared on the steepest eminences, and green streaks of corn emerged on the summits of the hills amid clusters of white rocks. Almost every spot of arable land appeared cultivated, even where no plough could possibly be employed. On enquiry we found that the spade was used in tillage where the country is very rocky and irregular.

As in Ireland, the potato crop failed in the mid 19th century, and a widespread outbreak of cholera further weakened the Highland population. The ongoing clearance policy resulted in starvation, deaths, and a secondary clearance, when families either migrated voluntarily or were forcibly evicted. There were many deaths of children and old people. As there were few alternatives, many emigrated, joined the British army, or moved to the growing urban cities, like Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Dundee in Scotland and Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Liverpool in England. In many areas people were given economic incentives to move, but few historians dispute that there were also many instances where violent methods were used by the landlords to clear the highland population.

As the 19th century progressed and the Battle of Culloden nearly a hundred years old, the privileges of the Highlander grew less and less. Lairds obtained greater rights with restriction on deer hunting, shooting for game such as grouse and blackcock, rights to the hills for sheep or cattle and even catching salmon from the streams or rivers being relaxed. Lairds saw a potential for making money out of these activities. Subsequently there became distinct division from lairds to common men, far different to the days of their forefathers.

The father of the Laird of Kindeace bought Glencalvie. It was sold by a Ross two short centuries ago. The swords of the Rosses of Glencalvie did their part in protecting this little glen, as well as the broad lands of Pitcalvie, form the ravages and clutches of hostile septs.

The clansmen bled and died in belief that every principle of honour and morals secured their descendants a right to subsisting on the soil.

The chiefs and their children had the same charter of the sword.

Some legislatures have made the right of the people superior to the right of the chief: British law- makers made the rights of the chief everything and those of their followers nothing. The ideas of the morality of property are in most men the creatures of their interests and sympathies. It must be said that the chiefs would have no land at all had it been possible for the clansman to predict how the Highlands would turn out. Sad it was that since the Union the laws preferred communities to consist of fewer people than to many, could this have been in fear that this could create another uprising having too many people in the same place together.

Large areas were being cleared of people across Scotland, lucky enough in Kintail where many of them were quite well off; one man was even a member for his county in what was considered the dominion parliament.

Others weren’t so lucky and endured the hardship of looking for alternative ways of earning money. The answer, unlikely as it may seem, was seaweed. Burning seaweed produced kelp ash, an alkali source, an important constituent in glassmaking at the end of the 18th century. It was also crucial in the textile industry: mixed with quicklime (CaO) it was used as a bleach; in soap form it washed wool and, for dying, it was an ingredient in muriate of potash (KCl). The requirements of shipbuilding led to legislation which prevented wood being burned to produce this so the seaware of the Western Isles became extremely attractive as an economic resource.

The kelp, though, did not come from just any seaweed washed ashore, the best sources lay underneath rocks some distance offshore which had to be cut by workers wading out and cutting it with scythes. It was then dragged ashore and dried, before burning, all in all a most labour-intensive activity and a most unpleasant one.

‘If one figures to himself a man, and one or more of his children, engaged from morning to night in cutting, drying, and otherwise preparing the sea weeds, at a distance of many miles from his home, or in a remote island; often for hours together wet to his knees and elbows; living upon oatmeal and water with occasionally fish, limpets and crabs; sleeping on the damp floor of a wretched hut; and with no other fuel than twigs or heath: he will perceive that this manufacture is none of the most agreeable.’

Second Report to the Commissioners and Trustees for Improving Fisheries and Manufactures in Scotland, 1755

Hard and unpleasant though the work was it was very lucrative, for the landlord that is, not for the worker. Hunter (in The Making of the Crofting Community) estimates the wages of the kelp harvester at between £1 and £3 per ton for the entire period from 1790 until the collapse of the industry. It was during this period that fortunes were made by the landlords who “owned” the kelp. Spanish barilla, which provided a larger proportion of alkali on burning was prevented from reaching the British market by the Napoleonic Wars. Kelp, therefore, reached prices of £20 per ton. As the entire manufacturing process was carried out by cheap island labour, this constituted pure profit for the landowners. Even the small cost of labour did not really need to be met: the labourers were crofters and either had a requirement to work so many days each year for their landlord or, alternatively, the kelping was deducted from their rent payments, so, as Hunter writes in Last of the Free,

‘It was little wonder, then, that landlord after landlord was prepared to subordinate all other land management considerations to the almost unbelievably lucrative business of making and marketing kelp.’

The landlord to benefit most from this industry was Lord Macdonald of Sleat. When he undertook a survey of his estates in Skye and North Uist in 1799-1800 he may well have felt that he did ‘not want to dismiss great numbers of his tenants’ in the reorganisation, as Eric Richards quotes in his favour, but that was in keeping with his surveyor, John Blackadder’s suggestion that, once the inland localities were cleared for sheep, those removed could be resettled on coastal crofts where ‘from the surrounding ocean and its rocky shore immense sums may be drawn .... As these funds are inexhaustible, the greater the number of hands employed so much more will be the amount of produce arising from their labour.’ |

To make sure that there would not be sufficient income in the farms alone for the displaced tenants, the new crofts were laid out on barren land ‘in the least profitable parts of the estate’, a situation helped in Skye by a proposed rent rise of 75% between 1799 and 1803.

The only thing which could interfere with this revenue stream for the financing of Armadale Castle was emigration and this was effectively halted by the 1803 Passenger Act. It reduced the number of passengers which could be carried on a vessel (by specifying a minimum amount of space for each) and established requirements for minimum levels of food, water and medicine to be carried on board. The net effect was to raise the minimum cost of a passage to Nova Scotia from £4 to £10 pricing it largely beyond the reach of Lord Macdonald and Clanranald’s tenants.

Lest it be thought that this is too cynical a view of the motives behind the act, these are the words of Charles Hope, its chief architect ,

‘I had the chief hand in preparing and carrying thro’ parliament an Act which was professedly calculated merely to regulate the equipment and victualling of ships carrying passengers to America, but which certainly was intended both by myself and other gentlemen of the committee to prevent the pernicious spirit of discontent against their own country, and rage for emigrating to America’

With the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the kelp monopoly was gone. Although tariffs protected it against Spanish imports for a while, these were soon abandoned and, in any case, the Leblanc process offered far cheaper sources of alkali. The industry collapsed and the need for a large and cheap labour force was gone. Many of the requirements of the 1803 Act were lost in new legislation in 1817 and emigration, which now suited the landlords, was made easier. By 1849, before beginning the brutal clearances of North Uist, best remembered for the events at Sollas, Macdonald would bemoan the fact that the island was so densely populated.

1800-1813 -- Extensive clearances in Strathglass, Farr, Lairg, Dornoch, Rogart, Loth, Clyne, Gospie, Assynt, and lower Kildonan.

1801 -- The first clearances of the Strathglass area by William, the 24th Chisholm. Nearly 50% of the Clan living there are evicted.

1801 -- The emigrant ship The Sarah sails from Fort William to Pictou. By contemporary laws, only 489 slaves would have been allowed to be carried in the ship's holds. But no such laws govern emigrants, and almost 700 people are crammed into the ship, with nearly 50 people dying on the journey and countless others falling ill.

1803 -- Seeing their labour-base diminishing due to emigration, landowners in the Hebrides work for passage of the Passenger Act, this limits the number of people who can immigrate to other countries, trapping and keeping many tenants in poverty.

1807 (Whitsun) -- Evictions at Farr & Lairg -- the first major Sutherlandshire clearances.

1807 (October) -- The Rambler, carrying 133 emigrants from Thurso, sinks in the Atlantic. Only three passengers survive.

1807 (November) -- a gathering of The Northern Association of Gentlemen Farmers and Breeders of Sheep agree to move their activities into Ross-shire, Sutherlandshire, and Caithness. This decision would lead to massive clearances in those areas.

1809 -- The Chisholm enacts another large clearance of his lands in Strathglass, advertising to interested sheep-farmers lots holding between 1,000 and 6,000 sheep.

1811 -- More than 50 shepherds are brought into Sutherlandshire and made Justices of the Peace -- thereby giving them legal control over the native tenants.

1811 - 1851 -- The demand for seaweed (or kelp) falls. The harvesting of kelp was taken up by many cleared farmers who were relocated to the coast of Scotland. The lowering demands for kelp returns those farmers to poverty.

1813 -- Lord and Lady Stafford, the landowners of Sutherlandshire, hire James Loch to oversee the clearing of their lands.

1813 -- Nearly 100 tenants of Strath Kildonan emigrate to Canada aboard the Prince of Wales and settle near Lake Winnipeg.

1813 -- Sir George MacKenzie of Coul writes a book justifying the clearances, citing: The necessity for reducing the population in order to introduce valuable improvements, and the advantages of committing the cultivation of the soil to the hands of a few....

1813 (Spring) -- Lady Stafford writes that she would like to visit her Sutherlandshire estate but: at present I am uneasy about a sort of mutiny that has broken out in one part of Sutherland, in consequences of our new plans having made it necessary to transplant some of the inhabitants to the sea-coast from other parts of the estate

1813 (spring) -- a group of Strath Kildonan residents march towards Golspie in order to have their grievances against the clearances heard. They are met by soldiers and the Sheriff, who, aided by local church ministers, intimidate the tenants into returning to their homes to await their eviction notices.

1813 (December 15) -- Tenants of the Strathnaver area of Sutherlandshire go to Golspie at the direction of William Young, Chief Factor for Lord and Lady Stafford. The tenants are told they have until the following Whitsunday to leave their homes and relocate to the wretched coastlands of Strathy Point.

1814 (April) -- Under the direction of Patrick Sellar, a Factor for Lord and Lady Stafford, heath and pastures surrounding Strathnaver are burned in preparation for planting grass for the incoming sheep. The native tenants of Strathnaver make no motion of moving to Strathy Point, or anywhere else.

1814 (June 13) -- Patrick Sellar begins burning Strathnaver. Residents are not given time to remove their belongings or invalid relatives, and two people reputedly die from their houses burning.

1815 -- The Sheriff-Substitute for Sutherlandshire arrests Patrick Sellar for:willfull fire-raising...most aggravated circumstances of cruelty, if not murder. Not surprisingly, a jury of affluent landowners and merchants acquit Sellar in April of this year.

1816. Soon after, Sellar continues clearing vast areas of Sutherlandshire.

1818 -- Patrick Sellar retires to his Sutherlandshire estate, given to him by Lord and Lady Stafford in acknowledgment of his work.

1819 (May) -- Another violent clearing of Strathnaver residents. Donald Macleod, a young apprentice stonemason witnesses: 250 blazing houses. Many of the owners were my relatives and all of whom I personally knew; but whose present condition, whether in or out of the flames, I could not tell. The fire lasted six days, till the whole of the dwellings were reduced to ashes or smoking ruins.

1819 (May) -- The Kildonan area is cleared. Donald MacDonald later writes: ...the whole inhabitants of the Kildonan parish, with the exception of three families--nearly 2,000 souls--were utterly rooted and burned out.

1819 (June) -- The Sutherland Transatlantic Friendly Association is formed to assist cleared tenants who wanted to emigrate to America. It generates little interest and soon folds.

1820 -- James Loch publishes his account of enacting the clearances, or, as he calls them, the improvements. He declares that Gaelic will become a rarity in Sutherlandshire.

1820 -- Journalist Thomas Bakewell severely criticizes both Loch's book and his actions during the clearances.

1820 (February and March) -- Hugh Munro, the laird of Novar, clears his estates at Culrain along the Kyle of Sutherland. A riot ensues when the Sheriff and military arrive to evict the tenants. Remonstrated by the minister Donald Matheson, the tenants eventually cease fighting and move away.

1821 (April) -- Officials bearing Writs of Removal for the tenants of Gruids, near the River Shin, are stripped, whipped, and their documents are burned. Fearing another riot like Culrain, military and police accompany the Sheriff back to Gruids where, faced with such strong opposition, the tenants gathered their few belongings and moved to Brora.

1821 showed an increase over the census of 1811 of more than two hundred... the county has not been depopulated--its population has been merely arranged in a new fashion. The (Duchess of Sutherland) found it spread equally over the interior and the sea-coast, and in very comfortable circumstances--(but) she left it compressed into a wretched fabric of poverty and suffering that fringes the county on its eastern and western shores.

1826 -- The Island of Rum is cleared except for one family. MacLean of Coll pays for the other natives to emigrate to Canada.

1826 -- The emigrant ship James arrives in Halifax. Every person on board had contracted typhus during the voyage.

1827 -- Lady Stafford visits her Sutherland estate and receives gifts from the tenants. Those gifts, wrote Donald Macleod, were provided by those who would subscribe would thereby secure her ladyship's favour and (that of) her factors -- and those who could not or would not were given to understand very significantly what they had to expect by plenty of menacing looks and an ominous shaking of the head.

1829 (September) -- The Canada Boat Song, a poem protesting the clearances, appears in Scotland's "Blackwood's Magazine."

1830 -- Lady Stafford visits her Sutherlandshire estate and visits the tenants living in primitive sheds. Unable to comprehend how people could live under such conditions, but speaking no Gaelic, she is not able to ascertain the condition of her tenants lives.

1830 (October 20) -- While stonemason Donald Macleod was off working in Wick, his wife and children were surprised in their home: ...a party of eight men...entered my dwelling (at) about 3 o'clock, just as the family were rising from dinner.

The party allowed no time for parley, but having put out the family with violence, proceeded to fling out the furniture, bedding and other effects in quick time, and after extinguishing the fire, proceeded to nail up the doors and windows in the face of the helpless woman.... Messengers had (previously) been dispatched--warning all the surrounding inhabitants, at the peril of similar treatment, against affording shelter, or assistance, to wife, child, or animal belonging to Donald Macleod. ...After spending most part of the night in fruitless attempts to obtain the shelter of a roof or hovel, my wife at last returned to collect some of her scattered furniture, and (built) with her own hands a temporary shelter against the walls of her late comfortable residence...(but) the wind dispersed (the) materials as fast as she could collect them.

Buckling up her children...in the best manner she could, she left them in charge of the eldest (who was only seven years old), giving them such victuals as she could collect, and prepared to take the road for Caithness (in search of her husband). She had not proceeded many miles when she met with a good Samaritan and acquaintance...Donald Macdonald, who, disregarding the danger incurred, opened his door to her, refreshed and consoled her, and still under cover of night, accompanied her to the dwelling of (a friend), William Innes...of Sandside. |

1832 -- Despite the fact that he forcibly evicted them, exiled members of Clan Chisholm swear allegiance to their chief back in Scotland.

1832 (late summer) -- Cholera runs through the Inverness area, claiming almost 100 lives. Many fear the illness came from the impoverished cleared tenants who beg on the streets, and strict laws are enacted to persecute these itinerants.

1833 -- At a party in honor of King William IV, Lord and Lady Stafford become the first Duke and Duchess of Sutherland.

1833 (winter) -- After the Duke of Sutherland's death, plans are made by some of the gentry for a monument to be erected in his honor. The tenants are "asked" to contribute, but Donald Macloed writes: all who could raise a shilling gave it, and those who could not awaited in terror for the consequences of their default.

1836 (autumn) -- a famine strikes the Highlands and Islands, leaving thousands to starve, despite efforts to fund emergency rations.

1837 -- The European historian/economist J.C.L.J. de Sismondi writes of Sutherlandshire: But though the interior of the county was thus improved into a desert--in which there are many thousands of sheep, but few human habitations, let it not be supposed by the reader that its general population was in any degree lessened. So far was this from being the case that the census of

1840 - 1841 -- Donald Macleod publishes a series of letters in the Edinburgh Weekly Chronicle, describing his own eviction and other eyewitness testimony of the clearances.

1841 (February) -- Henry Baillie, Parliament Member for Inverness, forms a committee to investigate the situation in the Highlands. The committee concludes that there are too many people living in the Highlands and that a course of aggressive emigration should be established.

1841 (August and September) -- Given writs of removal by legal officials, the tenants of Durness and Keneabin riot and attack police and sheriffs with stones and sticks. Only after being threatened with an onslaught of military troops do the tenants accept the writs and grudgingly move away.

1845 -- Denied shelter within the church itself and believing themselves to be cursed by God, ninety evicted tenants of Glencalvie take temporary shelter in the churchyard at Croick, and leave messages scratched into the glass windows: ...Glencalvie people the wicked generation... ...John Ross shepherd... ...Glencalvie is a wilderness blow ship them to the colony... ...the Glencalvie Rosses...

1845 -- The potato blight, which had devastated Ireland the previous year, wipes out most of the potatoes in the Highlands.

1846 (December) -- The Reverend Norman Mackinnon of Bracadale Manse wrote to the Chaplain in Ordinary to Queen Victoria: Oh, send us something immediately.... If you can send but a few pounds at present, let it come, for many are dying, I may say, of starvation...

1847 (February) -- James Bruce, a writer for "The Scotsman," reports that the Highlanders' problems are due to their own laziness and suggests the best solution is for the native tenants: as soon as they are able to labour for themselves, be removed from the vicious influence of the idleness in which their fathers have been brought up and have lived and starved.

1849 -- Despite some rioting by the native tenants, Lord Macdonald clears more than 600 people from Sollas on North Uist.

1849 -- Thomas Mulcok, a somewhat bizarre writer and journalist with the Inverness Advertiser arrives in the Highlands and vigorously attacks landlords and factors in print. So vigorously, in fact, that he eventually flees to France when faced with charges of slander.

1850s (early) -- Clearances of thousands of tenants in the Strathaird district, Suishnish, and Boreraig on Skye; and Coigach at Loch Broom.

1851 -- Sir John MacNeill, under the direction of the Home Secretary, tours the Highlands and reports back that the Highland poor are "parading and exaggerating" their poverty and are basically lazy. The only solution MacNeill sees is emigration.

1851 (August) -- The clearance of Barra by Colonel Gordon of Cluny. The Colonel called all of his tenant farmers to a meeting to "discuss rents", and threatened them with a fine if they did not attend. In the meeting hall, over 1,500 tenants were overpowered, bound, and immediately loaded onto ships for America. An eyewitness reported: "...people were seized and dragged on board. Men who resisted were felled with truncheons and handcuffed; those who escaped, including some who swam ashore from the ship, were chased by the police...." When officials in Glasgow complained to the Colonel about many of Barra's homeless wandering their streets, he stated: "Of the appearance in Glasgow of a number of my tenants and cottars from the Parish of Barra--I had no intimation previous to my receipt of your communication. And in answer to your enquiry--what I propose doing with them--I say 'Nothing'."

1853 -- Knoydart is cleared under the direction of the widow of the 16th Chief of Glengarry. More than 400 people are suddenly and forcibly evicted from their homes, including women in labor and the elderly. After the houses were torched, some tenants returned to the ruins and tried to re-build their villages. These ramshackle structures were then also destroyed. Father Coll Macdonald, the local priest, erected tents and shelters in his garden at Sandaig on Loch Nevis, and offered shelter to as many of the homeless as he could. Donald Ross, a Glasgow journalist and lawyer wrote articles outlining the clearance of Knoydart, which generated little sympathy.

1854 -- The clearing of Strathcarron in Ross-shire. Some Clan Ross women tried to prevent the landlord's police force by blocking the road to the village. The constables charged the unarmed women, and, in the words of journalist Donald Ross: "...struck with all their force. ...Not only when knocking down, but after the females were on the ground. They beat and kicked them while lying weltering in their blood....(and) more than twenty females were carried off the field in blankets and litters, and the appearance they presented, with their heads cut and bruised, their limbs mangled and their clothes clotted with blood, was such as would horrify any savage."

1854 -- Archibald Geike, describing a recent clearance on Skye, states he saw: (The house was) a wretched hovel, unfit for sheep or pigs. Here 6 human beings had to take shelter. There was no room for a bed so they all lay down to rest on the bare floor.

On Wednesday last the head of the wretched family, William Matheson, a widower, took ill and expired on the following Sunday. His family consisted of an aged mother, 96, and his own four children - John 17, Alex 14, William 11, and Peggy 9 - the old woman was lying-in and when a brother-in-law of Matheson called to see how he was, he was horror struck to find Matheson lying dead on the same pallet of straw on which the old woman rested; and there also lay his two children, Alexander and Peggy, sick! Those who witnessed this scene declared that a more heart

Matheson's corpse was removed as soon as possible; but the scene is still more deplorable. Here, in this wretched abode, and abode not fit at all for human beings, is an old woman of 96, stretched on the cold ground with two of her grandchildren lying sick, one on each side of her.

1854 -- An emigrant ship is described by "The Times" as: The emigrant is shewn a berth, a shelf of coarse pinewood in a noisome dungeon, airless and lightless, in which several hundred persons...are stowed away, on shelves two feet one inch above each other...still reeking from the ineradicable stench left by the emigrants on the last voyage... After a few days have been spent in the pestilential atmosphere created by the festering mass of squalid humanity imprisoned between the damp and steaming decks, the scourge bursts out, and to the miseries of filth, foul air and darkness is added the Cholera.

1854 -- Highland landowners are asked to gather troops from their tenants to fight the Crimean War. Most of the Highlanders refuse, one telling his laird: "should the Czar of Russia take possession of (these lands) next term that we couldn't expect worse treatment at his hands than we have experienced in the hands of your family for the last fifty years."

1856 -- The writer Harriet Beecher Stowe visits Sutherlandshire. Her tour is carefully orchestrated by the current Duchess of Sutherland to avoid sites of eviction, and so Stowe erroneously proclaims the tales of the clearances to be mostly fictional.

1872 -- A Parliamentary Select Committee is established to investigate claims that tenant farmers are being evicted in the Highlands to make room for deer. As the people had been cleared for sheep and not deer, the Committee finds no evidence.

1874 (spring) -- Starving tenants of Black Isle, Caithness and Ross areas attempt to commandeer grain shipments going from Lairds' estate farms to export ships. Military forces are called in to guarantee safe shipment of the grain.

|

|

As you can see in the chronology above, all the various events which occurred through the 18th and 19th centuries there are no words that could explain how tough life would have been. In some areas, whole glens were cleared, which today are as silent as they must have been when the landlord's factors had finished ruthlessly carrying out the orders of their masters. Homes were burnt and tenants forced to leave at the point of a sword or musket, carrying little or nothing as they headed towards a life of poverty and hunger.

There were two distinct types of 'clearance'. The first was a forced settlement on barren land usually near the sea. The crofts, as these plots of land became known, had very poor agricultural potential which the gentry wrongly assumed would be compensated for by fishing and seaweed harvesting, or kelping as it was called. From 1820, however, these areas were failing to provide any living. Kelp was not as saleable, fishing was poor yet rents were being pushed up. To cap it all came the 1844 potato famine.

New hardships from the first upheaval induced a second movement of people forced to attempt emigration. As the consequences of relocation were becoming apparent, insatiable landowners were still clearing and selling their estates without regard into the 1850s.

|

The second type of 'clearance' was often prompted by the failure of the crofts to produce a living for the Highlanders. It was a hopeless situation for many. The sheer number of people pushed to the coast coupled with huge rent increases, over-fishing and over-kelping resulted in destitution and starvation. When, in 1846, the potato crop failed many were left with no alternative, those who relied on potatoes felt hardship and had no alternative but to head for the bigger cities like Glasgow, Crieff and Edinburgh of course others followed in the footstep of those to try what they thought was a better life in a foreign land, emigrating south or emigrating to the colonies. [See emigrants and emigration]

In Knoydart, Ross, Skye and Tiree and most notably in the vast tracts of land in Sutherland owned by Elizabeth, Countess of Sutherland, the clearances were particularly noted for the violence used.

Two of the most notorious evictors were James Loch and Patrick Sellar [ See Main Oppressors]. Around 1820 demand for kelp and cattle dwindled and many tenants sank into rent arrears and apathy. In turn the rise in number of those unable to pay their rent encouraged landowners to evict the tenants from the marginal land leaving emigration as the only alternative. Lord MacDonald alone cleared most of North Uist and Skye or sold out to the infamous John Gordon of Cluny. Ships from ports from different parts of Scotland left for various destinations. [See emigrants and emigration]

Empowerment, Internationalism and Revolt

In 1873, John Murdoch, a retired Nairnshire excise man who had worked part of his life in Ireland, founded The Highlander newspaper to campaign on the Scottish cultural and land rights issue. He was certainly not the only significant campaigner, but we will focus here on his work because it is so perceptive and well documented. Not confined to simply managing the paper, Murdoch maintained close contact with the crofters and local communities by mostly walking from one township to another where ‑ often to the defiance and chagrin of landlords ‑ he would visit and campaign amongst the people. His tours accentuated more than ever the degree to which self-esteem and self-confidence were lacking amongst the Highland population, since often he was hard put even to gather a crowd, not because of lack of interest, but because of fear:

|

| "We have to record a terrible fact, that from some cause or other, a craven, cowed, snivelling population has taken the place of the men of former days. In Lewis, in the Uists, in Barra, in Islay, in Applecross and so forth, the great body of the people seem to be penetrated by fear. There is one great, dark cloud hanging over them in which there seem to be terrible forms of devouring landlords, tormenting factors and ubiquitous ground officers. People complain; but it is under their breaths and under such a feeling of depression that the complaint is never meant to reach the ear of landlord or factor. We ask for particulars, we take out a notebook to record the facts; but this strikes a deeper terror. 'For any sake do not mention what I say to you,' says the complainer. 'Why?' We naturally ask. 'Because the factor might blame me for it.' |

|

Where once there were proud and independent societies with their own Gaelic tongue, now a subjected population had succumbed to what later critics would recognise as a culture of the oppressed with the English language forced through the education system. Afraid openly to discuss their plight, the Highland peoples had internalised their oppression to a degree that they were unable even to voice their complaints, let alone have them recorded.

Murdoch saw that the way forward was cultural regeneration, for without a social empowerment focused upon the linguistic and cultural identity of Highlanders he saw little potential for advancement in land reform or political emancipation. Murdoch's campaign of empowerment was far more than the basic development of a class consciousness or a political front. What he was seeking was more attuned to a spiritual awakening. Donald Meek, professor of Celtic at Aberdeen University, in an analysis of Murdoch's theological foundations for land reform, sees in his work and that of other such campaigners of the time a precursor to the liberation theologies of Paulo Friere, Gustavo Guttierez and others of Latin American and Southern African origin. Extensive use was made of biblical texts like Leviticus 25, "The land shall not be sold in perpetuity, for the land is mine," and Isaiah 5, "Woe unto them that join house to house, that lay field to field, till there be no place...." An increasingly interested London based press later stirred the national conscience over such sentiments, for instance, the Pall Mall Gazette of 24th December 1884 quoting the campaigners that: "The Earth is the Lord's, not the landlord's...."]

Murdoch concluded that, "The language and lore of Highlanders being treated with despite has tended to crush their self-respect and to repress that self-reliance without which no people can advance." The effects of "alien rule" and the experiences of land enclosure and eviction had created a "very provoking fear universally present among the people" who were consequently "afraid to open their mouths." Foreshadowing ideas that were adopted by the Highland Land League, he urged:

"Our Highland friends must depend on themselves and they should remember that union is strength.... We do not advocate that they should fight or use violent means, for there is a better way than that. Why do they not form societies for self-improvement and self-defence? Did they become, they would become conscious that they possess more strength than they are aware of."

Linking the enclosure of the Highlands with the subjugation of people overseas, he declared earlier in 1851, "The dying wail of the cheated redman of the woods rings in our ears across the Atlantic." And later whilst constantly criticising British imperial policy in Highlander editorials, he was always quick to show that the crofters' struggles were synonymous with those of oppressed peoples around the world. On hearing the news of Britain's invasion of Afghanistan, for instance, he declared: "What glory is to be had from fighting semi civilised but brave and patriotic highlanders? Noble Afghan highlanders, our sympathies are with you!" Above all, he emphasised that "the cause of the Highland people is not dealt with in an exclusive and narrow spirit, far less in antagonism to other people." The key issue was in an awakening of spirit that allowed Highlanders to enter the wider world: "Their sympathies are widened, their views are elevated, and they learn to stand erect, not only as Highlanders, shoulder to shoulder, but as a battalion in the great array of peoples to whom it is given to fight the battles incident to the moral and social progress of mankind."

Having studied land tenure patterns around Europe ‑ Norway, Belgium and Switzerland ‑ he was able to point out that superior social relations abounded elsewhere, the "peasant proprietorship" canton system of Switzerland making it "perhaps the most enlightened, independent and prosperous country in Europe." The comparisons to Britain and Ireland made it "very surprising that we, who profess to be in the van of progress, and the highest degree of liberty, should be content to be in the most unsatisfactory state, with regard to land, of almost any nation in Europe."

In 1881 the Land Bill for Ireland granted security of tenure and fixed rents. Murdoch sarcastically noted how the Duke of Argyll's resignation from the Government in protest was "one of the strongest proofs of the beneficent character of the measure" and he emphasised how the co‑ordinated campaign of resistance which lead to the Bill was "suggestive of many practical thoughts to every Highlander." Within a week, however The Highlander was forced to close under financial pressure. But within a further month the crofters on Captain William Fraser's Kilmuir Estate used Irish Land League tactics to compel a reduction of their rent by 25%. Soon after, and somewhat in emulation of an earlier (1874) crofters rent riot on Bernera, Lewis, Lord MacDonald's tenants at Braes, Skye, mobbed a visiting sheriff officer. Lead, as was so often the case in crofter direct actions, by a woman, Mairi Nic Fuilaidh, they forced him to burn the court eviction summonses he had come to deliver. Thus the Skye Rent Strike marked the start of the remarkably non‑violent "Crofters Wars". Ten days later, 17th April 1882, arrests were made. Mud and stones were thrown when 47 imported Glasgow police faced a crowd of over fourteen hundred protestors who had arrived from all quarters of Skye lead by their respective pipers. Recognising that state authority was losing its grip, the British Government responded to Sheriff Ivory's call for help by action which was to be repeated on a number of occasions in the Highlands and other colonies: it sent in the gunboats with police reinforcements, over four hundred marines and one hundred bluejackets.

|

"This impressive demonstration of force was met with polite passive resistance as people conspicuously dug their potatoes at every township along the coast. The Glasgow Herald correspondent observed, 'The district was found in a state of the most perfect peace, with every crofter minding his own business'."

In February 1883 the Highland Land League was founded in London to apply political pressure in Westminster and organise mass rent strikes, demonstrations, and support for reform by constitutional means by friends at home and abroad. The government's response was to set up a Royal Commission to enquire into the complaints of the crofters. Headed by Baron Francis Napier, an Anglican Tory landowner with considerable experience of colonial problems in India, it reported later in the year and vindicated the legitimacy of the people's grievance. In the General Election of 1885 the crofters took advantage of the extension of the franchise and returned five crofter Members of Parliament. Finally, in 1886 the Crofters Act was passed, giving for the first time heritable security of tenure with controlled rents on those smallholdings defined as being of crofting status.

The 1886 Act fell far short of returning to the people land which had formerly been taken from them. By far the greatest areas of land remained completely outwith crofting tenure. But the Act did secure the survival of crofting life into the present era. It was not until 1976 that the Crofting Reform Act gave the crofter the right to buy the freehold of their land at 15 times the holding's fair rent. There was no rush to take this up, since freehold entailed perceived breach of community solidarity and loss of privileged crofting status with the agricultural grants which accompanied it. Also, the law was widely misinterpreted as meaning that the landlord also had to be paid 50% of the development value of the land. Resolution of this misinterpretation was to prove vital in subsequent events leading up to community land ownership at Assynt. It was not until the passing of the 1991 Crofter Forestry (Scotland) Act that crofters could apply for permission to plant trees on their land. Trees planted outwith this provision are the property of the landlord, which is one reason why, traditionally, few crofts had any forest shelterbelts.

Pre-eminent in contemporary literature was Sir Walter Scott, a prolific writer of ballads, poems and the historical novels. His romantic portrayals of Scottish life in centuries past still continue to have a disproportionate effect on the public perception of "authentic Scottish culture," and the pageantry he organised for the Visit of King George IV to Scotland made tartan and kilts into national symbols. George MacDonald also influenced views of Scotland in the latter parts of the 19th century.

Claims that some writers are coruscating in their condemnation of the Clearances, seeing the process as an early version of "ethnic cleansing". However, writer Ross Noble believes this approach over-simplifies the issues involved. Under the economic and social ideas of the several centuries involved, landowners and employers were generally callous about the 'lower orders', (exemplified by the 1843 fictional character of Ebenezer Scrooge) and these modern terms such as 'genocide' and 'ethnic cleansing' reflect new sensitivities and social perspectives, which in this case would not apply, as most of the landlords were fellow Scotsmen.

However, considering that by the end of the eighteenth century the Scottish landlords had, for the most part, been born and raised in London, they would have held the same unflattering opinion of the Highlanders that the majority of those living in England and Southern Scotland held. Therefore, "ethnic cleansing" certainly cannot be ruled out by a simple inspection of ancestry.

It was only in the mid-nineteenth century that the second, more brutal phase of the Clearances began; this was well after the 1822 visit by George IV, when lowlanders set aside their previous distrust and hatred of the Highlanders and identified with them as national symbols. However, the cumulative effect was particularly devastating to the cultural landscape of Scotland in a way that did not happen in other areas of Britain.

While the collapse of the clan system can be attributed more to economic factors and the repression that followed the Battle of Culloden, the widespread evictions resulting from the Clearances severely affected the viability of the Highland population and culture. To this day, the population in the Scottish Highlands is sparse and the culture is diluted, and there are many more sheep than people. Although the 1901 census did return 230,806 Gaelic speakers in Scotland, today this number has fallen to below 60,000. Counties of Scotland in which over 50% of the population spoke Gaelic as their native language in 1901, included Sutherland (71.75%), Ross and Cromarty (71.76%), Inverness (64.85%) and Argyll (54.35%).Small but substantial percentages of Gaelic speakers were recorded in counties such as Nairn, Bute, Perth and Caithness.[ see also Gaelic language] |

What the Clearances started, however, the First World War almost completed. A huge percentage of Scots were among the vast numbers killed, and this greatly affected the remaining population of Gaelic speakers in Scotland.

The 1921 census, the first conducted after the end of the war, showed a significant decrease in the proportion of the population that spoke Gaelic. The percentage of Gaelic speakers in Argyll had fallen to well below 50% (34.56%), and the other counties mentioned above had experienced similar decreases. Sutherland's Gaelic-speaking population was now barely above 50%, while Inverness and Ross and Cromarty had fallen to 50.91% and 60.20%, respectively.

However, the Clearances did result in significant emigration of Highlanders to North America and Australia — where today are found considerably more descendants of Highlanders than in Scotland itself.

One estimate for Cape Breton, Nova Scotia has 25,000 Gaelic-speaking Scots arriving as immigrants between 1775 and 1850. At the beginning of the twentieth century, there were an estimated 100,000 Gaelic speakers in Cape Breton, but because of economic migration to English-speaking areas and the lack of Gaelic education in the Nova Scotian school system, the numbers of Gaelic speakers fell dramatically. By the beginning of the 21st century, the number of native Gaelic speakers had fallen to well below 1,000.

Appalachia a mountainous region of the eastern United States, also served as a destination for displaced non-gentry Gaels, including many Irish, and bears the cultural marks of the immigrant peoples. Gael communities settled chiefly in a broad arc extending through the states of Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

The Balmorality Epoch: The Great Sporting Estates

The final stage of consolidating present patterns of enclosed land tenure came after the military demand for wool collapsed with the ending of the Napoleonic Wars. As Iain Mac a'Ghobainn immortalises in his epic poem, "Spirit of Kindness," soldiers returning from Waterloo were prone to finding that their families had been cleared in their absence. Remaining unenclosed lands had been consolidated with former sheep farms to make the Great "Sporting" Estates. By 1912, 3, 599,744 acres or one fifth of the entire Scottish land mass had been converted so that "gentlefolk" versions of great white hunters could engage in one sided mortal battle with the stag, salmon, grouse and the thrush-sized snipe.

In his sociological study of the athletic and bagpiping competitions which characterise today's Highland Games, Jarvie] shows how the new sporting landlords took control of such traditional gatherings of the clans to consolidate their social status. Cultural regeneration could then be seen as deriving from the benevolence of the ruling classes, thereby lending landlords a pseudo authentic role analogous to that of the chieftains of the past.

The Highlander, like the native American and African, had once been caricatured as barbarous and uncivilized. The traveller, John Leyden, typifies such an outsider perspective. Returning to Perth in 1800 he wrote, "I may now congratulate myself on a safe escape from the Indians of Scotland...."Few early travellers had the ability to see beyond the racial stereotype. An exception was the Swiss geologist, Necker de Saussure, who in 1807 recorded his astonishment at finding on Iona, "under so foggy an atmosphere, in so dreary a climate, a people animated by that gaiety and cheerfulness which we are apt to attribute exclusively to those nations of the South of Europe." But for most of the ruling class, the second half of the nineteenth century became instead a time when the Highlanders could safely be patronised in terms of "the glamour of backwardness" and presented "in terms of loyalty, royalty, tartanry and Balmorality." Trend‑setting lairds (landowners) like Queen Victoria, with her Balmoral Castle retreat, displayed the stunning contradiction of, on the one hand, professing a love of Highland scenery and culture; whilst on the other hand patronising emigration programmes and setting in process damaging land management regimes centred around deer and grouse.

A look through the Highland press quickly reveals that now, in the mid‑1990's, summary dismissals, evictions, expensive procedural delays in planning matters and demolition of housing remain very much a part of estate control over communities. The West Highland Free Press, for instance, gives careful documentation on 30th April 1993 of how the estate factors (legal managers) of one of the world's richest absentee landlords, Sheik Mohammed bin Rashid al Maktoumm of Dubai, have bulldozed houses in his Wester Ross "glen of sorrow" to prevent human habitation, probably because of "the night-time poaching activities of the local population." Twelve family homes have been reduced to rubble in a district which has 800 applicants on the local authority housing waiting list. The Sheik retains a certain support in some quarters because of his large donations to small local charities.

1948 (November) The Knoydart area was originally cleared in 1853 by Josephine MacDonell and the former tenants were sent to Nova Scotia. Ninety-five years later, on 9-Nov-48, seven men who had served in World War II staked out claims on the Knoydart property, saying it was their right to stake out crofts on land that was being purposely left to go to waste. In the ensuing months, the 7 men gained the support of the populace, mostly due to the pro-Nazi philosophies of the then Knoydart laird, but a Court ruling eventually forcibly evicted the men. |

1976 -- Crofters are legally allowed, for the first time, to purchase their own croft farms.

1993 -- The 130 tenant residents of Assynt raise £130,000 and, with the assistance of various grants and loans, buy their 21,000 acre homeland when it goes up for sale by the landowner. The Assynt Crofters Trust Ltd is established to oversee the land, instead of the traditional laird. A spokesman for the Trust states: "On the 1st February 1993 we became the first crofting communities to take complete control of our land. Our success means that we have put an end to the stranglehold of absentee landlords on the Crofting communities of North Assynt and set in motion an irresistible change in the land tenure system throughout the Highlands and Islands of Scotland.".

1994 -- Mr. Sandy Lindsay, a resident of Inverness and a former SNP councillor, initiates a movement to have the 27-foot red sandstone statue of the Duke of Sutherland that sits atop Ben Bhraggie in the Golspie area, destroyed or removed.

Lindsay considers the statue offensive to the descendants of the tenants that the Duke removed from his lands. Lindsay gathers worldwide support and a petition is presented to the Highland Council's Sutherland Area Committee in May of 1996. The Council rejects the petition, but agrees to construct a series of information plaques describing the Clearances in the Ben Bhraggie/Golspie area.

1996 -- The Pictou Waterfront Development Corporation begins an effort to construct a replica of Hector, an emigration ship that brought 200+ passengers to Canada from Ross-shire.

1996 -- According to Auslan Cramb's Who Owns Scotland?, the top twenty landowners of Scottish lands are:

Domestic:

The Forestry Commission = 1,600,000 acres

Duke of Buccleuch/Lord Dalkeith: 4 estates in the Borders = 270,000 acres

Scottish Office Agriculture Dept: 90% crofting land = 260,000 acres

National Trust for Scotland: (including the 75,000-acre Mar Lodge) = 190,000 acres

Alcan Highland Estates: land used for electricity generation = 135,000 acres

Duke of Atholl, Sarah Troughton: Estates around Dunkeld/Blair Atholl = 130,000 acres

Capt. Alwyn Farquharson: Invercauld on Deeside & smaller estate, Argyll = 125,000 acres

Duchess of Westminster, Lady Mary Grosvenor: = 120,000 acres

Earl of Seafield: Seafield estates, Speyside = 105,000 acres

Crown Estates Commission: 3 main estates, including Glenlivert = 100,000 acres

International:

Andras Ltd, Malaysia: Glenavon, Cairngorms/Brauen, Inverness = 70,000 acres

Mohammed bin Raschid al Maktoum: = 63,000 acres

Kjeld Kirk-Christiansen, head of Lego, Denmark: Strathconon, Mid Ross = 50,000 acres

Profs Joseph and Lisbet Koerner, Swedish Tetra Pak heiress: Corrour, Caithness = 48,000 acres Stanton Avery, USA: Dunbeath, Caithness = 30,000 acres

Mohamed Al Fayed: Balnagowan, Ross and Cromarty = 30,000 acres

Urs Schwarzenberg, Switzerland: Ben Alder, Inverness-shire = 26,000 acres

Count Knuth, Denmark: Ben Loyal, Sutherland = 20,000 acres

His Excellency Mahdi Muhammad al-Tajir, UAE: Blackford, Perthshire = 20,000 acres

Prof. Ian Roderick Macneil of Barra, USA: Barra and islands = 17,200 acres

Land Restitution

Today throughout Scotland, just 4,000 people own 80% of private land. This figure would represent 0.08% of the resident population were it not that many are absentee landlords ‑ English aristocrats, Arabian oil sheiks, Swiss bankers, South African industrialists, racing car drivers, pop stars, arms dealers and others not noted for their socio‑ecological awareness. They include entertainers such as Terry Wogan and Steve Davis; pension funds such as Rolls Royce, the Post Office, Prudential Insurance and the Midland Bank; overseas interests like Sheik Mohammed bin Rashid al Maktoum of Dubai, Mrs Dorte Aamann‑Christensen, the Jensen Foundation and the Horsens Folkeblad Foundation from Denmark, and Paul van Vlissingen of the Netherlands. A 1976 study concluded that some thirty‑five families or companies possess one third of the Highland's 7.39 million acres of privately owned land.

During the Thatcher dominated 1980's, land prices spiralled as more and more people, whose personal lifestyles and corporate activities had destroyed their own countryside, wanted to buy into Scotland. Communities seemed powerless as to who controlled them and what happened to the ecology. The current turning point was perhaps most marked in 1985 by the formation of the Scottish Crofters Union. This, along with a cultural renaissance which started to see many young people recovering their history, music, language and poetry, as well as recognition of the growing social and ecological bankruptcy of mainstream Western life, has lead to fresh awareness of the potential to organise in mutual solidarity, drawing on old roots of community and place.

|

In 1991 a crofter from Scoraig in the West Highlands, Tom Forsyth, established a charitable trust with the seemingly grand objective of bringing ownership of the Isle of Eigg under community control. With co‑Trustees Lis Lyon, Bob Harris and Alastair McIntosh, the Trust received an unprecedented 73% vote of confidence in the community ownership proposals. (Previous communities, like that on the Isle of Rassay, had lacked confidence to push for self‑determination.) The Eigg islanders had resented the showmanship, control and paternalism of the existing landlord, Keith Schellenberg, "Scotland's best known English laird," who once boasted that "Somehow it seemed more important to beat the Germans at Silverstone than to deal with a little Scottish island. The race put it all in perspective." Islanders feared getting an even worse replacement, like the previous laird, who had made life "like living under enemy occupation."

The Eigg Trust failed in its 1992 bid to raise sufficient funds to secure purchase, not least because Schellenberg undermined the effort by saying he would not sell into community control. One could imagine how popular he might have been with his landowning friends had he set such a collaborative precedent. But what the Trust did demonstrate, and this was to be important in subsequent events elsewhere, was that the market for what he had called a "collector item" estate could be spoiled by the glare of publicity. As one news report of Eigg put it, "a private buyer is not exactly going to get a welcoming party." This effect was confirmed when one of the Trustees phoned up Savills, the top people's estate agents, and asked about the dangers of the Eigg Trust to the Scottish land market. One Jamie Burges‑Lumsden replied: